Full BF16 Training (Mostly) Works Now. Until It Doesn’t. Enter Stochastic Rounding.

Or: why your loss curve sometimes rage-quits at step 3,000 and it’s not “just bad luck”.

Not long ago, “training in low precision” had the vibe of a questionable street food stall. Everyone knew it was faster and cheaper, but nobody wanted to be the person who ends up hugging the toilet at 3 a.m. So we did the responsible thing:

We ran mixed precision.

Parameters in FP32, compute in FP16, a second copy somewhere for safety, and a constant sense that VRAM was being used like a Victorian-era coal furnace.

It worked. Mostly.

It was also mildly depressing. Because you’d look at your GPU memory and think: I am paying for all this silicon and still can’t fit the model I actually want.

Fast-forward to now: full BF16 training is no longer a niche daredevil hobby. Plenty of setups converge out of the box. People run big experiments, sleep at night, and don’t even mention it in the paper because it’s become… normal.

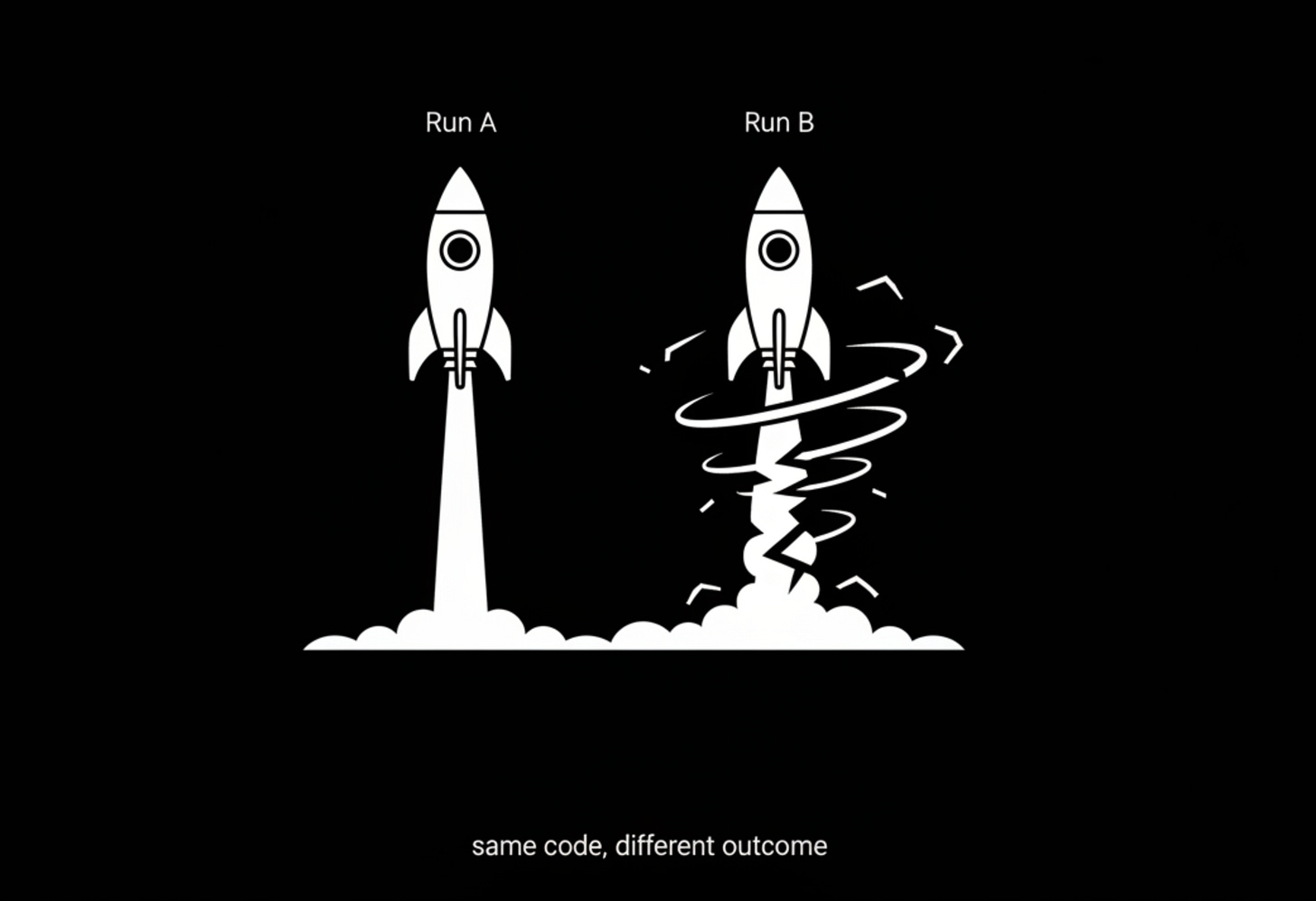

And then you hit the other timeline.

The one where the run does not converge.

The one where your loss turns into modern art.

The one where someone says “try lowering the LR” like they’ve contributed something meaningful to society.

So what do you do when full BF16 doesn’t behave?

You stop arguing with the universe and you fix the part that’s actually broken.

The inconvenient truth: the worst BF16 problems often come from updates, not gradients

There’s a classic assumption people carry around: “low precision hurts because the forward/backward is noisy.”

Turns out: not quite.

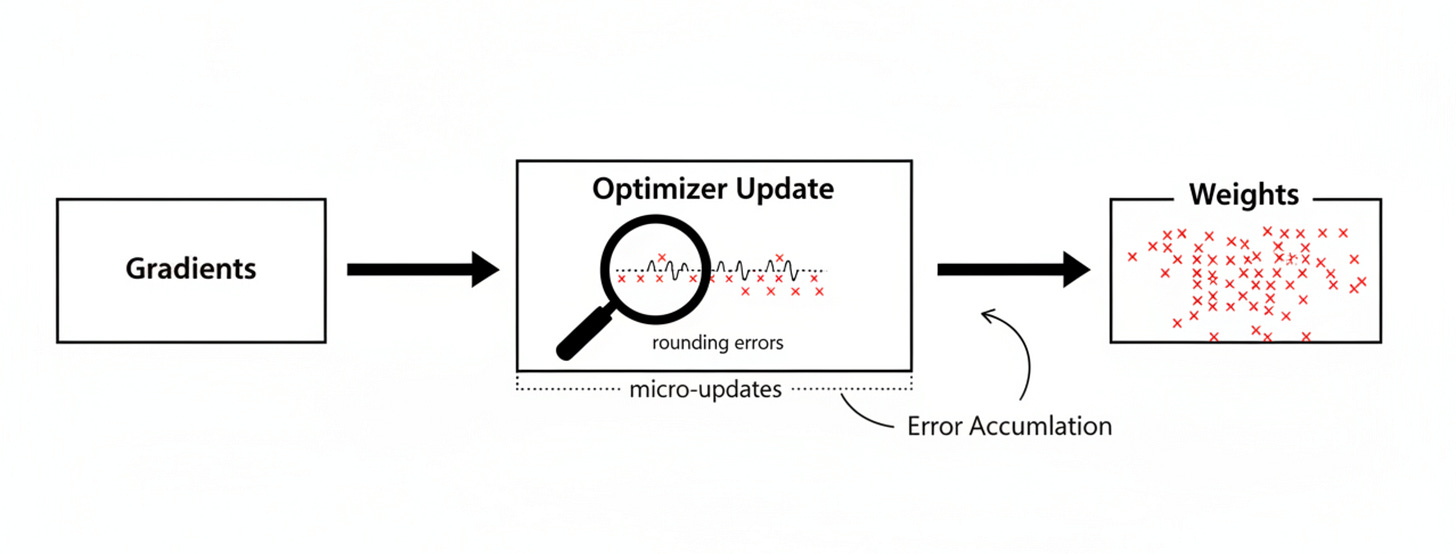

A solid (and slightly under-appreciated) paper from 2020 points out that the real damage often happens during parameter updates—where rounding errors accumulate in a biased way—while rounding during gradient computation is relatively less harmful. Here’s the paper.

In plain terms: your gradients can be “good enough,” but your updates might be quietly sabotaging you.

Which brings us to the core villain: rounding.

Before the “smart” fix: the boring engineering fixes (that you should still try)

If your full BF16 run is unstable, start with the standard “make the system less fragile” moves:

1) Accumulate gradients in FP32

Both:

within a data-parallel group (DP), and

across gradient accumulation steps (multiple forward/backward passes)

And yes, PyTorch is heading toward making this nicer: separate dtype for params vs grads is coming in PyTorch 2.10 (already in nightly 2.10).

This is one of those changes that will quietly save thousands of hours of human life.

2) Do optimizer math in FP32 (even if params live in BF16)

A lot of optimizer implementations already cast states/params/grads to FP32 during the update step (not the same as storing everything in FP32, but still helpful). Example in torchao Adam.

These tricks often get you from “exploding” to “fine.”

But sometimes you still get the nightmare run.

Which is when you need the fix that feels like cheating, because it’s so simple.

Stochastic Rounding: the rounding that stops lying to you

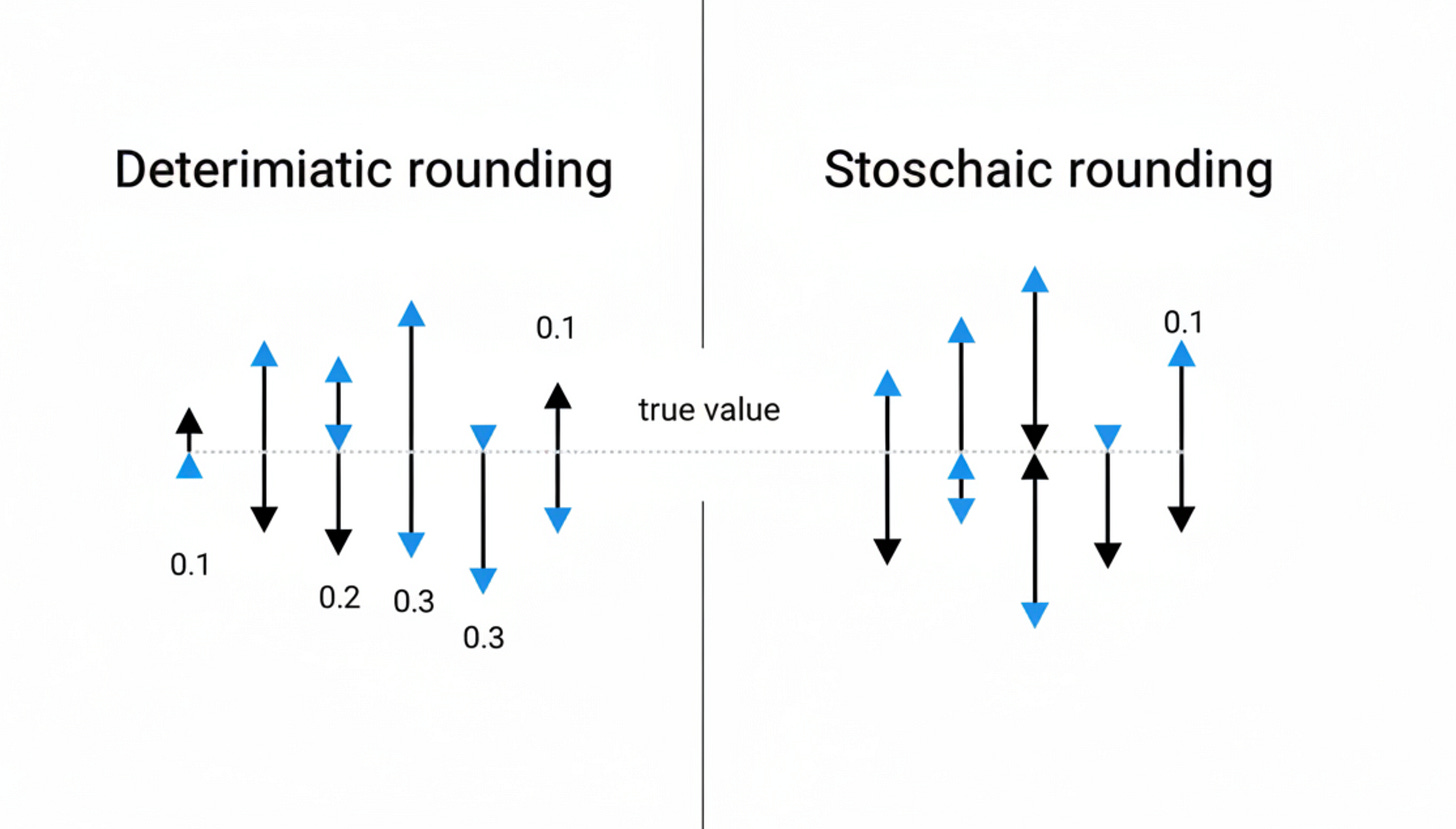

Normal rounding is “locally” sensible. It minimizes immediate error.

It’s also biased over time, because it always pushes values in a predictable direction based on where they fall on the representable grid.

In training, “predictably biased” is exactly what you don’t want.

Stochastic Rounding (SR) flips the logic:

If your true value sits between two representable BF16 values, you don’t always round to the nearest one.

Instead, you round up or down with probability proportional to the distance to each endpoint.

The magic property:

It’s unbiased.

In expectation, it preserves the original number:

E[SR(x)] = x

That one line is the whole point. You’re trading a tiny bit of randomness for the removal of systematic drift.

And yes, there’s newer work that actually validates full BF16 + SR in practice, connects SR to regularization effects, and proposes an AdamW variant with SR.

The mental model that makes SR click

If standard rounding is like a manager who always “rounds down your bonus because it’s easier,” stochastic rounding is like a manager who flips a weighted coin and says:

“Sometimes you win. Sometimes you lose. But over time, it averages out.”

It’s not nicer. It’s fairer.

Training cares more about “fair over time” than “perfect right now.”

Where SR actually matters (and where it doesn’t)

This is the key optimization insight:

SR is most valuable when applied to parameter updates in low precision.

SR during forward/backward exists, but a lot of evidence suggests the bigger failures come from update rounding error accumulation.

So the practical recipe tends to look like:

compute updates in FP32

apply updates to BF16 params

use SR during the FP32 → BF16 copy/update step

Implementation notes: the part everyone forgets in distributed training

If you’re doing distributed training, SR introduces a new problem:

RNG synchronization.

If each process uses different random rounding decisions, your replicas can diverch diverge. And not in a cute “stochasticity helps generalization” way. In a “your training is now undefined behavior” way.

So: make sure all processes share a consistent RNG stream or otherwise ensure deterministic equivalence of SR rounding across the DP world.

A PyTorch SR snippet (for the brave)

You gave a compact SR-style implementation idea (essentially adding noise in mantissa bits before truncation). The important part isn’t the exact bit-twiddling — it’s the principle: add randomness so the truncation is unbiased.

If you want a real production-grade baseline, the easiest path is to crib from the torchao SR optimizer implementation, which does the sane thing:

cast params/states/grads to FP32

compute the AdamW update in FP32

write params back to BF16 using SR (optionally)

Paper with implementation references and torchao is here

So what should you do on Monday morning?

Here’s the playbook that doesn’t waste your week:

Step 1: Try full BF16 “as is”

If it converges, smile and pretend you’re a genius.

Step 2: If it’s unstable, do “boring” FP32 safety rails

FP32 grad accumulation

FP32 optimizer math

watch for inf/nan sources (grad clipping, loss scaling policies, etc.)

Step 3: If it still fails, assume the villain is update rounding bias

Add Stochastic Rounding at the BF16 update boundary.

Step 4: Measure properly

Don’t just watch loss. Track:

divergence rate across seeds

training stability at higher LRs

final quality vs baseline

step-to-step variance

SR is often less about “higher peak” and more about “fewer catastrophic runs.”

Which is exactly what you want in real training pipelines.

Closing thought: BF16 isn’t the problem. Silent bias is.

People talk about low precision like it’s “noisy compute.”

But the more interesting story is this:

Your model isn’t dying from noise.

It’s dying from systematic rounding drift applied millions of times, quietly, at the moment you update the thing you care about most: the weights.

Stochastic rounding is not glamorous. It doesn’t have a flashy benchmark name. It doesn’t come with a demo video.

It just stops the math from slowly lying to you.

And in machine learning, that’s basically half the job.